Examining Work Cultures That Deliver Higher Productivity

Examining Work Cultures That Deliver Higher Productivity - Beyond the buzzwords What culture actually means for getting things done

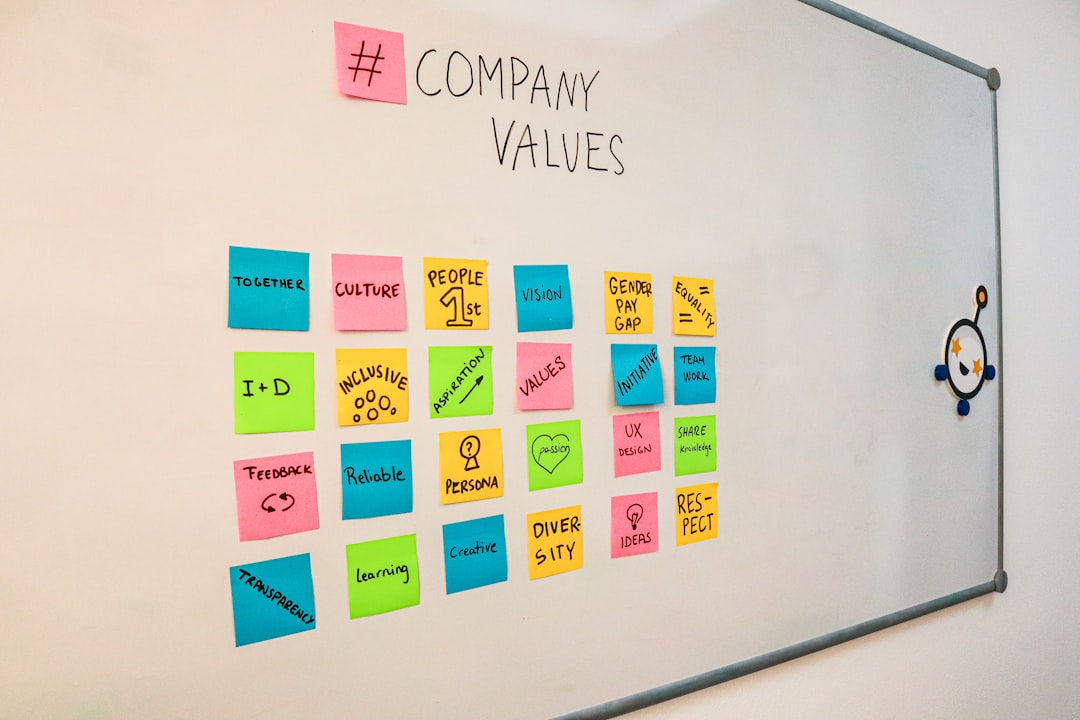

Discussions around workplace culture often get bogged down in feel-good language that sounds good but doesn't shed much light on what it actually means for getting work done. Beyond the common corporate speak, culture isn't some abstract concept declared from above; it's the sum total of how people truly behave day-to-day. It's in the real-world dilemmas employees face and how they're encouraged or expected to navigate them, the level of trust built between colleagues, and whether people genuinely feel supported in tackling their tasks. Moving past generic slogans to foster actual behaviors and interactions – the nitty-gritty of how things happen here – is what truly enables a more productive environment. It's about grounding the idea of culture in the practical realities of work.

Observing how work actually gets done suggests that what's often labelled "culture" involves several less obvious dynamics:

Beyond posters and mission statements, this collective 'culture' appears to subtly hardwire how individuals interpret information, gauge acceptable risks, and the pace at which decisions are actually made day-to-day. It's effectively a pervasive filter on reality and action within the organization.

Datasets often indicate that environments fostering a sense of safety to voice ideas or concerns (often termed psychological safety) and embracing candid feedback loops correlate with fewer operational slip-ups and apparently quicker collective navigation of problems. This implies a functional efficiency linked to interpersonal trust dynamics.

Pinpointing the real impact of culture on productivity requires looking past articulated values; the most tangible indicators are the routine ways people behave and interact within the organization—the unwritten rules governing daily operations. The enacted norms seem to matter far more than the declared ones.

Initial findings connect less stressful and more supportive workplace climates to reduced instances of employees being absent or merely present but unproductive (presenteeism). This indirectly seems to preserve overall team capacity and consistency of contribution over time.

Teams where members share a clear, consistent understanding of objectives, roles, and workflows—possessing strong internal 'shared mental models'—appear to execute complex tasks with notably better synchronization and faster overall progress. It's like a shared cognitive map accelerating collaborative efforts.

Examining Work Cultures That Deliver Higher Productivity - Does a healthier workplace really translate to more widgets

It's a persistent idea that tending to employee health straightforwardly boosts tangible output, often framed as producing more 'widgets'. However, charting a clear line from general wellbeing to a direct uplift in measurable productivity faces complexities. While initiatives aimed at physical and mental health might influence factors like attendance or general mood, converting these into consistent, higher operational throughput isn't automatic or easy to quantify. The effectiveness of focusing on workplace health in genuinely influencing output seems highly dependent on how these efforts are truly woven into the daily fabric of work and the overall functioning environment. The degree to which a healthier setting translates into more productivity appears less about implementing isolated programs and more about the subtle, integrated ways it genuinely fosters an environment conducive to sustained higher performance.

Stepping back to look at environments described as 'healthier' – moving beyond broad concepts to observable factors like light, movement, and interaction styles – research continues to probe how these might genuinely impact output. The connection isn't always a straight line, but accumulated data points to several intriguing correlations, suggesting mechanisms through which workplace well-being elements could affect something as tangible as the rate of production or quality.

For instance, studies observing office layouts have indicated that access to natural light or even just views of outdoor green spaces might do more than make a space pleasant. Preliminary findings suggest this environmental factor could play a role in improving employee concentration spans, potentially leading to a quantifiable reduction in the kinds of small errors that can hold up progress on detailed tasks. The exact neural pathways are still being mapped, but the correlation appears more than coincidental.

Similarly, initiatives supporting physical activity or better sleep hygiene aren't purely about individual welfare outside work hours. The thinking here is that better physical recovery and energy levels could translate into more sustained focus and manual dexterity, where relevant. While linking a specific gym program directly to widget output is complex, aggregate data implies a connection to fewer defects reported in quality control checks and perhaps a reduction in certain types of operational mishaps attributed to fatigue or lapses in attention.

Another area explored is the degree of control individuals feel they have over their work. When people are afforded greater say in how or when certain tasks are completed – within necessary constraints, of course – it seems to tap into intrinsic motivators. This isn't just about being 'happy'; it's posited that this sense of agency can make individuals more resilient and persistent when tackling complex problems or facing setbacks. The argument follows that this internal drive could lead to higher sustained rates of output on demanding projects, potentially pushing through difficult phases more effectively than those feeling micro-managed.

The role of social connections within teams also appears critical, not just for morale, but for endurance. Strong, positive relationships among colleagues seem to function as a significant buffer against the cumulative stress and strain of demanding work environments. This doesn't necessarily mean being best friends, but having functional, supportive interactions. The logic is that this social resilience helps individuals weather tough periods without burning out prematurely, thereby contributing more consistently and for longer periods to the collective effort.

Finally, encouraging a mindset and environment where continuous learning is valued seems to foster more than just updated skill sets. It appears to cultivate adaptability and mental agility. When confronted with novel problems or needing to pivot on a project, teams with a strong learning orientation seem better equipped to process new information and devise effective solutions more rapidly. This capacity to learn and adapt quickly appears to directly influence the speed at which new challenges are overcome or processes are improved, ultimately impacting the overall pace of innovation and problem resolution. These various elements, while seemingly distinct, suggest a complex interplay where well-being factors could subtly underpin the practical realities of productivity.

Examining Work Cultures That Deliver Higher Productivity - The flip side Cultures that actively hinder rather than help

Turning to the other end of the spectrum, certain work environments can actively obstruct progress rather than facilitating it. Where deep-seated mistrust or a culture of blame prevails, individuals often become guarded, withholding crucial information or avoiding necessary challenging discussions. This isn't just a matter of discomfort; it leads to systemic blind spots where problems fester unaddressed and collective intelligence is deliberately suppressed. Furthermore, environments that severely punish any misstep or deviation from established routine can instill a debilitating fear of failure. This doesn't encourage careful work; it crushes initiative and experimentation, critical for adapting to changing circumstances or finding better ways of doing things. The outcome is often a painful inertia, where outdated practices persist long past their utility because challenging them feels too risky, ultimately acting as a drag on the collective capacity to get meaningful work done or evolve effectively.

Yet, looking closely reveals environments where the collective way of working appears to actively impede achieving goals, rather than facilitate them. It's the other edge of the productivity blade.

Consider the measurable impact when fear and uncertainty become pervasive. Our observations suggest that in settings where punitive reactions to mistakes are the norm, a significant portion of cognitive capacity seems rerouted. Employees exhibit behaviors consistent with constant threat monitoring, which inherently reduces the mental bandwidth available for engaging with complex analytical tasks or fostering the kind of exploratory thinking needed for innovation. This isn't just anecdotal; the data hints at a tangible drain on high-level processing power, diverting energy away from the core work requirements.

Similarly, examining settings characterized by heavy-handed oversight, often labeled micromanagement, illustrates another kind of systemic drag. Rather than speeding things up, this approach seems to effectively disable the internal problem-solving engines of individuals. When every minor decision requires external validation, people appear to cease proactive identification of issues or independent course correction. The consequence observed is often a paradoxical stagnation, where workflows bottleneck waiting for approval, and employees default to passive execution, reducing overall system agility and resilience to unforeseen challenges.

Where the flow of information is consistently unclear or priorities remain vaguely defined, the system incurs substantial overhead. Data suggests employees in such environments spend disproportionate amounts of time attempting to decode expectations, reconcile conflicting directives, or simply understand the current state of play. This continuous effort to establish clarity functions as a significant cognitive tax, consuming mental resources that could otherwise be directed towards productive task execution, leading to delays, rework, and palpable frustration.

From an engineering perspective, a culture quick to assign fault appears fundamentally detrimental to process improvement. When the penalty for admitting error is high, the system loses its primary mechanism for self-correction: reliable feedback on failures and near-misses. Necessary data points for identifying systemic weaknesses or flaws in standard operating procedures are suppressed. This blockage in the organizational learning loop means the same issues are likely to recur, preventing the kind of iterative refinement essential for long-term efficiency gains and robust operational performance.

Finally, while seemingly counter-intuitive, environments that glorify or mandate excessive work hours consistently correlate with diminishing returns. Data compiled across various industries indicates that pushing beyond sustainable limits leads to an increase in cognitive fatigue. This fatigue manifests not only as reduced output volume after a certain point but, critically, as a noticeable decline in the quality and accuracy of the work produced. The physiological toll directly compromises the precision and sustained focus required for effective task completion, suggesting a clear point where more time spent simply doesn't equate to more value delivered.

Examining Work Cultures That Deliver Higher Productivity - Looking at the numbers Correlation between cultural characteristics and employee contribution

When examining the data available, a connection between the typical ways people operate within an organization – essentially its working culture – and indicators of how individuals contribute is often observed. Studies using various metrics tend to suggest that the collective feel and everyday interactions within a workplace environment correlate with measures of employee performance and factors like their presence or absence from work. While many reports point towards a positive association – implying that certain established cultural patterns align with what appear to be better contribution metrics – it's important to understand that the vast majority of numerical investigations reveal correlation rather than definitively proving direct causation. Attempting to isolate precisely how a specific cultural trait reliably leads to exact quantifiable changes in output remains a complex undertaking. This complexity is partly because broader influences, such as societal backgrounds individuals bring or the dynamics inherent in diverse groups, also factor into the numbers being analyzed. Consequently, although the available data suggests relationships exist, drawing a simple, firm cause-and-effect line from a single cultural characteristic to a precise employee contribution number is frequently an oversimplification of the reality of intricate workplace dynamics.

Examining data suggests some intriguing, sometimes counter-intuitive, correlations between the collective 'how we do things' and the resulting output and efficacy of individuals within an organization. These are less about espoused values and more about observable patterns of interaction and response.

Chronic exposure to work environments characterized by erratic demands or inconsistent expectations – essentially a culturally embedded unpredictability – correlates with documented physiological stress markers. This biological response isn't benign; it appears linked to a measurable degradation in executive cognitive functions. Specifically, the capacity for deliberate planning, task sequencing, and maintaining attention on intricate details seems to suffer, potentially manifesting as increased error rates or decreased efficiency in tasks requiring sustained mental effort, an observation sometimes borne out in structured cognitive assessments conducted in simulated work contexts.

In cultures where deference to formal authority is a strong implicit norm, data trends often show a significantly lower frequency of employees proactively identifying and raising operational risks, systemic inefficiencies, or potential points of failure to higher levels within the structure. This suggests that potentially critical data points regarding system health and opportunities for improvement are less likely to enter the collective problem-solving loop, hindering the organization's ability to perform real-time course correction or optimize processes based on dispersed local knowledge.

Navigating subtle, yet persistent, negative interpersonal dynamics or experiences requiring significant emotional and cognitive expenditure to manage appears to consume a measurable portion of an individual's available mental processing power. This constant requirement for self-regulation effectively taxes cognitive resources, verifiably reducing the capacity available for proactive task engagement, deep analytical work, or creative problem-solving that demands sustained, unfettered concentration.

Workplace norms that implicitly or explicitly discourage asking probing questions, challenging existing assumptions, or questioning 'how things are done' correlate with a slower rate at which factual discrepancies, inconsistencies in data, or emerging workflow exceptions are identified and subsequently propagated as actionable information within a team or across systems. This delay in detecting and disseminating critical 'state' information creates data asymmetry, leading to downstream errors, duplicated efforts, or delayed decision-making cycles.

Finally, the unspoken cultural stance on process discipline – whether it values speed and workarounds over adherence to established procedures or standardization – statistically correlates with quantifiable metrics like system defect rates, the frequency of unplanned rework cycles, or the average time it takes to resolve technical or operational issues. A culture implicitly tolerating deviation from agreed-upon methods appears to accumulate 'operational debt' over time, directly impacting the long-term stability, maintainability, and efficiency of the overall system.

More Posts from specswriter.com:

- →The Evolution of Symbolic Expression in Human Culture From Cave Paintings to Digital Art

- →7 Essential Components Every Account Management Template Should Include in 2024

- →Unveiling the Importance of MTTF A Critical Metric for Non-Repairable Asset Reliability

- →7 Key Confluence Features for Streamlined Technical Documentation in 2024

- →Step-by-Step Guide Setting JAVA_HOME on Windows 11 in 2024

- →The Evolution of Knowledge Bases From 1950s Card Catalogs to Modern AI-Driven Repositories